REVISED EDITIONS

Being a writer has often been compared to

having homework every night for the rest of your life. That being the case, then being an editor can

perhaps best be compared to having to mark that homework.

It’s a little over the twelve months since I first

started working as an editor for Crooked Cat Publishing. I’d recently completed an online course in

Editing and Rewriting, under the expert tutelage of the wonderful Dr

Calum Kerr.* I’d originally

signed up for the course with a view to being able to cast a more critical eye

over my own work, but I came away from it with two further thoughts in

mind. The first was a burning desire to

channel the interminable rantings of my Inner Grammar Geek into a force for

good. The second was that if I can’t

make it as a writer myself, then at least I might be of some small use to those

who can.

Since then, I’ve been asked several times:

What exactly does an editor do?

In short, the editor is the author’s

right-hand man (or in my case woman) who works closely with the author to

produce a pristine manuscript which will, in turn, become a published

work. One of the biggest problems with

being a writer is the danger of becoming so involved with one’s own work that

one loses all sense of objectivity.

(Take this from one who knows.

Been there, done that, spilled coffee all down the T-shirt, and then

again all down the clean one I put on in its place…) This is the point at which

the writer needs an extra pair of eyes.

The editor, who is in the privileged position of being the first person

to see the manuscript in the capacity of the reader, is that extra pair of

eyes.

An editor is much more than just a

proofreader. True, an editor does need

to keep an eagle eye open for typos, spelling mistakes, punctuation slips and

grammar gaffes – but the editor also needs to be on the lookout for other things

that don’t necessarily fall within the proofreader’s remit. These might include:

- Continuity

errors. For example, an object which is

red in one scene suddenly and inexplicably becomes green in another.

- Factual

errors. A large flock of robins is seen happily feeding on a lawn. Robins are territorial, so this would never

happen in real life.

- Inconsistencies

of character. Why would a lifelong

vegetarian be seen happily tucking into a large steak?

- Loose

ends left dangling. If an object is

lost, either it needs to be found, or a plausible reason must be given for its

failure to reappear.

- Dangling

modifiers. “A man in a red car wearing a

black coat” could mean that coat is being worn by the car rather than the man.

- Possible

issues of copyright when quoting from other sources.

- Sentences

or paragraphs which need to be split or reformatted because they’ve come out

too long or complicated. Like I’ve just

had to do with this one, in fact.

- Passages

where some details might need more clarification. This happens when an idea has formed in the

author’s head, but has never actually made it on to the page.

This last problem is surprisingly common, and

when it crops up, the author (often working in the mistaken belief that the

reader automatically knows as much as the writer does) usually doesn’t see

it. I once beta-read a novella for a

writer friend who couldn’t believe that I didn’t understand why one of the

characters had behaved in a particular way.

Said friend insisted that the motive behind it had been explained – but

when asked to point out exactly where, was forced to admit that no, it hadn’t.

|

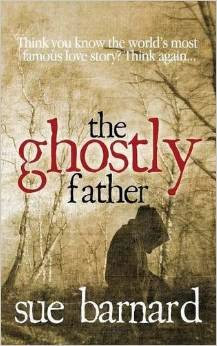

| Sue's novel |

One of the editor’s other tasks is to make

suggestions for improvement to the text, such as tightening up dialogue, or getting

rid of superfluous words or phrases, or sometimes changing the structure of

sentences so that they read more easily.

This is achieved by judicious use of the “Track changes” feature in MS

Word. This wonderful tool is the

e-quivalent of the teacher’s red pen.

Changes suggested by the editor appear on the manuscript highlighted in

red. The manuscript is then returned to

the author, who has the choice of accepting or rejecting those changes. The author then might suggest more changes

(which show up on the manuscript in blue), and returns the document to the

editor. Rinse and repeat as

necessary. When both author and editor

are completely happy with the result, the final (squeaky-clean) manuscript is

then returned to the publisher.

After that, a proof is returned to the author

for checking. This final check is very

important, as typos or formatting errors can still creep in at this late

stage. And, without wishing to sound

disrespectful to other members of my honoured profession, it is not unknown for

editors to make mistakes. One infamous

example of this took place a few years ago, and the unfortunate victim of this

particular editorial blunder was none other than JK Rowling. The first print-run of Harry Potter and the Goblet of

Fire contained a glaring continuity error, which, until it was subsequently explained,

baffled Rowling’s readers for a long time.

The mistake (which was corrected in later editions of the book) did not

appear in her original manuscript. It

was introduced by one of her editors.

Come to think of it, editing is, in many

ways, a bit like housework. Nobody ever

notices it – unless it’s done badly.

*Dr

Kerr has asked me to point out that although the Editing &

Rewriting course is not currently running, it will soon be available as a

textbook/how-to book.

As well as being a member of Crooked Cat’s

editorial team, Sue is a published and award-winning poet, and the author of

two novels: The Ghostly Father

(which was nominated for the 2014 Guardian First Book Award) and Nice Girls Don’t. Both are available in paperback and e-book

form.

You can read her blog here.

Great post - thank you both. Editors are often the unsung heroines of great books!

ReplyDeleteThank you! I had no idea, until I started doing it, just how much is involved!

DeleteFantastic - got me wanting to go to that Doctor now too - and I know how hard editing is without beating authors to death with sarcasm!

ReplyDeleteWelcome to my world, Cameron! ;-)

DeleteGreat explanation, Sue. It's a good check-list for an author to keep handy. ;-)

ReplyDeleteThanks Nancy. Glad to hear you found it useful. :-)

DeleteGreat blog, Carol and Sue, and very interesting. I find it easier to spot mistakes in someone else's work than in my own. Very informative article.

ReplyDeleteDon't we all? But then, I'm probably worse than most, because I'm a complete nitpicker!

DeleteAll I know is that she's an absolute slave driver...

ReplyDeleteGET BACK TO WORK!

DeleteWonderful info. Sue & Carol - thanks.

ReplyDelete:-)

DeleteThanks, Carol, for introducing us to Sue Barnard, and a clear explanation of the editor's role in bringing a manuscript up to a professional standard. And thanks, Sue, for that list - very handy.

ReplyDeleteThanks Teagan. Hope it's useful! :-)

ReplyDeleteSue, you sound like an amazing person to have behind any writer but I can't entirely identify with your first sentence. For me writing is a therapeutic activity. I love doing it. If it felt like homework I would stop. As for the editing, I have had the experience of publication from both sides, traditional and self-publishing. I truly did not appreciate the amount of work that went into editing until I recently self-published. It has got to be the most difficult, most unpleasant job I've ever done and, as an ex-teacher I can honestly say that it's far harder than having to mark essays every night. I applaud you!

ReplyDeleteThank you Rosalind. I too find writing very enjoyable and therapeutic. The idea about it feeling like homework was not my own - it's a meme which does the rounds on Facebook from time to time. Having said that, I've worked as a freelance copywriter, and when I was given a title, a word-count and a deadline, there have been times when it did feel a bit like writing essays! But when I can please myself about what I write, it definitely doesn't feel like homework.

ReplyDeleteI'm full of admiration for teachers. If I had to spend my evenings marking mountains of essays, all on the same subject, I think I'd very quickly go completely crazy. I remember my French teacher at school telling us that when she was marking exam papers she could only do three or four at a time. This was because seeing the same mistake over and over again made her more and more irritated, and she recognised the danger of getting more and more punitive with the marking.

At least with editing, it only involves one work at a time!

I echo every word of that Sue. My first editor - back in 1983 at what was then Macdonald /Futura - was and still is a very real friend.

ReplyDeleteThank you Beryl. How lovely to know that! :-)

DeleteHow did I miss this? I never miss a Pink Sofa blog! Well, I'm so glad I've read it now. Sue sounds like someone I would love to have behind me too. Wonderful that she is both a writer and an editor - and such a dedicated editor too. Thanks for the intro CarolStar!

ReplyDeleteThanks Val! If by "dedicated" you mean "ultra-fussy," you've summed me up very well!

ReplyDeleteInteresting. There's so much to be said in favour of editors, particularly when it comes to non fiction.

ReplyDeleteThanks Jenny. Although I've occasionally written non-fiction pieces, editing them for other people is still uncharted territory. Having said that, editors do need to be on the lookout for factual errors in fiction. I know of at least one other editor who managed to miss a pretty fundamental one which went on to make it into print - to the author's eternal frustration!

DeleteI've never tried editing non-fiction, Jenny. Though I have caused several fiction writers to have an "Oh Sh*t!" moment!

ReplyDeleteYou're never done editing really. I've even been at readings of my books and wanted to tweak as I read out. As an editor myself I'm getting fussier - about my own work too.

ReplyDeleteWho was it who first said "The price of pedantry is eternal vigilance"? I think those words will probably appear on my tombstone.

DeleteSeriously, though, we have to call a halt somewhere - otherwise we'd never get out of bed in the morning. We'd certainly never make it into print!